LIBRARIES MATTER

On the train home from Raleigh the other day, I was counting the trampolines out the window when it hit me that of the six North Carolina cities I’ve called home, four have stops along the path of the Amtrak Carolinian. I know this state, thanks to 20 years as a writer and editor with several newspapers and two magazines, including Our State and Charlotte, that introduced me to people along every hill and holler and waterway.

The moment you believe you have a place figured out—particularly when that place is in the American South—is precisely the time to worry about what you don’t know.

Apologies to my beloved train, but I’ve found no better place to be humbled than the Library. And I’ve found few library systems more vital to the future of the region and country than Charlotte Mecklenburg’s. I’ve held library cards in Forsyth, Guilford, Wake, and Cumberland counties, but something about this one feels different.

It feels big, and I don’t mean in terms of its 20 physical branches and the virtual branch. I mean big in that it’s the axis of knowledge in the fastest-growing city in the Southeast, a city that hosts NBA All-Star games and political conventions, the largest city in a changing state in a changing region, a city of protests and prayers and patios. Charlotte’s a place where smart people live and where smart people want to be, and where all of those different ideas and viewpoints must be expressed and heard and catalogued, and what better place is there for all three than the Library?

If you’ve even flown through Charlotte in the past five years, you’ve heard that the city ranks 50th out of 50 in terms of upward mobility, meaning it ranks last among major U.S. cities for children hoping to rise out of poverty in their lifetimes. I’ve heard it so many times that I can’t tell if the phrase “50 out of 50” is a source of shame or a marketing campaign. Probably both. Either way, the response to the ranking, which came out in 2014, has been tremendous: millions raised for affordable housing projects and early childhood education, dozens of new leaders from communities that once had no voice. Around the country, people who study mobility are following Charlotte’s aggressive response to see if it can be replicated.

That’s where we live, a place that has a problem and the potential to solve it.

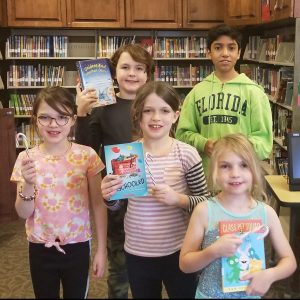

Inside the walls of the Library, and inside the portal of the Library’s website, you’ll find representations of the problems and the solutions. The Library offers daily comfort to people who need affordable homes. The Library, perhaps more than any other organization, provides free internet access to people who can’t afford it—nearly 837,000 people accessed library WiFi last year, a 31.2 percent increase from the year before. The Library is helping move our children toward the crucial third-grade literacy goals—attendance in the system’s pre-third-grade literacy programs was nearly 232,000 last year, up 11.8 percent. And the Library has the uptown North Carolina Room, which is my favorite room of all because it explains how we got here.

The Library is a starting point for mobility.

***

When I talk to people who love libraries, two words that make me cringe are “nostalgia” and “relevant.”

Let’s start with nostalgia. When I was in elementary school in the 1980s, my favorite author was Matt Christopher, who wrote such literary classics as The Kid Who Only Hit Homers and The Catcher With The Glass Arm. Some 25 years later, I was a professional writer and working with a new editor named Glenn. I went to visit Glenn in Vermont one spring, and in his personal library he keeps all the books he’s authored or edited over the years. I knew most of the work. But I was stunned to see a row of Matt Christopher books. Turns out, Matt Christopher became a franchise after my childhood, and now, years after he died in 1997, other writers now “co-author” Matt Christopher books. Glenn has co-authored several.

I’ll never forget the moment when I realized my new editor was also the new Matt Christopher. But that story isn’t about “nostalgia.” It’s about a connection. That connection I made as an adult wouldn’t have happened without the childhood connection to the library. Libraries, personal and public and otherwise, are the keepers of stories, and stories will always bond us.

That leads to the other word.

“Relevant” is one of the few words in the English language that always seems to be playing defense against its antonym. To be relevant is to suggest that irrelevance is always waiting outside with the hearse door open.

“Essential,” though, plays offense. The only way to make it negative is to add the prefix “non,” and that attaches like an ugly addition to an otherwise handsome house. “Essential” is too lovely for that, too important to be anything but essential.

The Library is essential. Now more than ever. In Charlotte more than anywhere.

To understand where you live and why it is the way it is, few web pages in this city are more valuable, more essential, than the Resources page on the Library’s website. Here a Library card-holder has access to everything from a full list of North Carolina’s General Statutes, to entrepreneurship and military databases, to archives of The Charlotte Observer back to 1892, The Charlotte Post back to 2006, and to editions of The New York Times or The Wall Street Journal from the 1980s through today.

Tired of screens? The Library arranges handshakes, too. This year’s Community Read of The Hate U Give engaged thousands and was topped off by a visit from the book’s author, Angie Thomas, in March. And in January the Library was a partner in a community conversation around Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, that brought more than 1,000 people to First Baptist Church West.

The Library can introduce you to people outside your neighborhood and to perspectives outside your generation. It is, then, not a nostalgic place that happens to be relevant. Instead, in a city where we need more understanding of our past and current neighbors, the Library is an essential connector.

***

Complacency breeds assumptions, and assumptions are the preamble to hard lessons. Our burden as Charlotte residents is that people from different parts of town don’t interact with each other, and just in the past few years, we’ve had several high-profile moments of ignorance that cost people top positions, spots on athletic rosters, and votes in elections.

The Library is a defense against that. And a cure for that.

The allure of ignorance is strong. Politicians and cable media companies profit from dumbing down the electorate, profit from convincing you that you’re just a collection of opinions on only a dozen or so topics. Google and Facebook add to the troubles by narrowing you into boxes based on likes and previous searches.

The Library invites you out of your algorithm. The Library reminds you that the world is a three-dimensional place. In the Library you find flesh and nuance, and curiosities you never knew were worth chasing.

The Library is one of the last decent places where different ideas intersect. And in Charlotte, one of the most crucial intersections in the country, we celebrate decent places. The Library isn’t here to argue your point, but to present you with more information about it. The Library, truly, doesn’t care what you believe.

The Library, truly, doesn’t care what you know.

The Library’s here to ask: What is it, then, that you don’t know?

Michael Graff is a freelance writer in North Carolina. He was the executive editor of Charlotte magazine from April 2013 to August 2017, where he remains a columnist. His writing work has appeared in Our State, Washingtonian magazine, Politico, and on SB Nation Longform, along with many others.

This article originally appeared in The Charlotte Observer on July 26, 2019.